Rotation

Contents

Applications

Worked examples

© The scientific sentence. 2010

Formulas

θ = (1/2) α t2 + ωot + θo

ω = α t + ωo

ω2 - ωo2 = 2 α (θ - θo)

ar = ω2(t) r

at = α r

Circ. Unif. motion:

1 rev = 2π rad

θ = ωt

v = ω r

T = 2π/ω = 1/ƒ

ar = ω2r = v2/r

at = 0

|

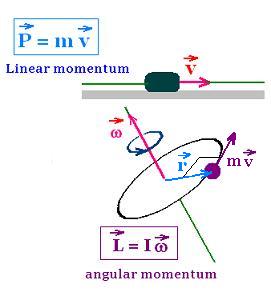

| Angular momentum

1. Angular momentum

A force exerted on an object, that can be translated,

causes its linear velocity to change: F = m a. A torque

exerted on an object, that can be rotated, causes its

angular velocity to change τ = I α. Any object

can rotate about an axis.

Let's recall that a moment(of force) is the tendency

of the force to oscillate or rotate an object; and the

momentumis the quantity of motion of an object.

Linear momentum if the motion of the object

is linear and uniform; and angular momentum when

the motion of the object is circular. The linear momentum is

a vector quantity as the velocity v is; and the angular momentum

is also a vector as ω is. A linear momentum "P" has the same

direction as the linear velocity v . The direction of the angular

momentum "L" is the direction if the angular velocity "ω".

The direction of ω is on the rotation axis. This direction

is perpendicular to the plane from where the angular momentum

stems; that is the plane formed by the position vector and the

linear velocity (then linear momentum) of the object. We remember

that the moment of inertia of an object is relative to an axis;

whereas the torque and the angular momentum are relative to a

reference point. The concept of angular momentum is very

useful in rotational dynamics.

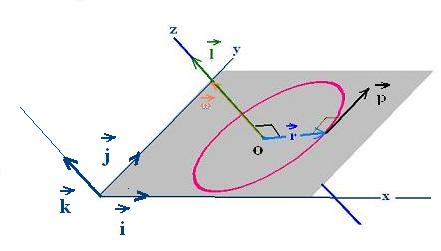

2. Angular momentum of a single particle

The angular momentum "l" of a particle about a referenec point O is

defined as:

l = r x p

where r is the position vectore of the particle measured from O;

and p is its linear momentum. The cross product shows that the

linear momentum is a vector quantity. It is perpendicular to the plane

containing r and p. Its direction is defined by the right-hand rule.

Its dimension is [mass][length2][time -1]; and

its SI unit is kg.m/s. Its magnitude is = mrvsinθ, where

θ is the angle formed by r and p in this order. Recall:

The angular momentum is relative to reference point about

which is defined and then calculated.

The simple case is when a particle travels in a circle of radius r.

The angular momentum is the determined about the center of cercle,

that is here, the point of reference. In circular motion, at each

point of the circle, the velocity v is perpendicular to r,

therefore θ = 90o and the expression of the

angular mmentum takes the following simple form:

l = r x p = r x mv = m r x v = m r v sin θ = mrv

Since v = ω r, we have then:

l = mr r ω = mωr2

If the vectors r and p are contained in the plane xy,

l will point in the z-axis. Its direction depends on the

sense of the rotation. It is given by the right-hand rule.

Viewed from the + z direction, if the motion is counterclockwise,

l is toward + z, hence lz is positive. If the motion

is clockwise, l is toward -z, and lz is negative.

This is exacly the direction of ωz. If k

is the unit vector of the z-axis, we can write:

l = lz k = mωzr2 k

If the motion is also uniform, ωz will be

constant equal to ω arewe will have:

l = lz k = mωr2 k

In an inertial frame, the second Newton's law is writen as ΣF = ma, where

ΣF is the net force exerted on the particle of mass m,

and a the produced acceleration. In terms of linear momentum,

this equation is written as: ΣF = dp/dt; that is the

derivative of the linear momentum p of the particle. In

rotational motion, the net force ΣF exerted on a

particle produces a torque a net torque Στ

= r x ΣF, where r is the position vector of the particle

nad ΣF is the net force exerted on the particle.

We want to link this τ to angular momentum l of the particle.

With l = r x p. The time derivative of the angular momentum is:

dl/dt = dr/dt x p + r x dp/dt

The first term der/dt x p =0 because dr/dt = v, and

v x p = m v x v = 0. Therefore:

dl/dt = r x dp/dt = r x ΣF = Στ

We obtain, therefore an important formula:

Στ = dl/dt

The net torque exerted on a particle relative a point is equal

to the time rate of change of its angular momentum relative to that point. The

angular momentum is measured in an inertial frame .

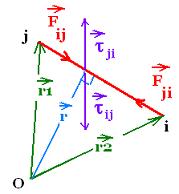

2. Angular momentum of a system of particles

For a system of particles, the total angular momentum L relative to

a reference point is equal to the vector sum of individual angular momenta

li all relative to that same point, that is L = Σli.

The time derivative of L is: dL/dt = Σdli/dt =

Σ(Στi) (sum for all particles, and the

sum of all torques for each particle, that is the sum for all

particles of their net torques). This sum of net torques is equal to:

- The sum of the internal torques on the particles due the forces

they exert on each other within the system, which they cancel in pairs

(according to the Newton's third law: Fij = - Fji

and τij = - τji)

- The sum of external torques.

Therefore, the total net torque is equal to the external net torque.

dL/dt = Στext

Only external torques can change the angular momentum

of a system. The torques and the angular momentum are measured

about the same reference point in an inertial frame.

Recall an object rotates about a fixed axis. Its angular velocity

ω and its moment of inertia are referred to an axis; whereas

torque and angular momentum are both relative a refrence point.

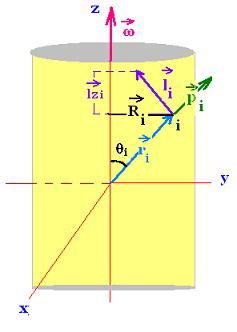

3. Angular momentum of a rigid object

We want a relation between the moment of inertia relative

to a fixed axis and the angular momentum of a rigid object

with sufficient symetry relative to a point in this same axis.

It we choose the z-axis (or axial) about the rigid object rotates,

the component of the angular momentum of the object is Lz =

Σliz. The z-comonent of the angular momentum of the particle i is

li= ri x pi = miviri sin (ri, vi)

ri and pi are perpendicular, so:

li = miviri

Since vi = ωz Ri, and Ri = ri sinθi we have then:

li = miωz Riri

and liz= miωz Ririsinθi = miωz Ri2

li has both an axial and radial component. It doesn't depend

of the location of the origin in the axis. Its expression is valid

for any origin as long as the origin is on the axis.

Therefore:

Lz = Σliz = Σ miωz Ri2 = ωz Σ mi Ri2 = ωz I

Lz = I ωz

Iz is the moment of inertia of the rigid object relative

to the z-axis of rotation.

With an abject that has sufficient symetry, the radial components

within the object cancel, so L is parallel to lz. We have then:

L = I ω

3. Equation of motion for a rigid object

rotating about a fixed axis

Taking the time derivetive of the above

equation giges:

dLz/dt = I dωz/dt = I αz

But dLz/dt = Στext, so

Στext = I αz

This the equation of motion of a rotating rigid object

about a fixed z-axis.

|

|